Top 10 Queer and Feminist Books of 2013

2013 has been truly awesome for new queer and/or feminist things to read. Here are some of the best ones.

The Top 10 Queer/Feminist Books of 2013

10. How Poetry Saved My Life, by Amber Dawn

Amber Dawn combines memoir and poetry into something that is both at once as she discusses her experiences as a writer, sex worker, survivor and queer-identified person.

In her interview with Ali, Dawn says:

“Many memoirs cover a chronological time frame—travelling from the author’s “inciting moment,” through a sort of character or personal arch, to an ending resolution. I think this popular memoir formula is much too tidy to capture most of our lives, especially if our lives are under-represented in the mainstream. Plus, I didn’t have the emotional strength to write a chronological memoir about sex work and survivorship. Poetry offered me a language of beauty and dynamism to write out my more vulnerable ideas and experiences. I’ve always felt comfort in reading and writing poetry. Poetry is the closest thing I have to a spirituality.”

9. The Summer We Got Free, by Mia McKenzie

The Summer We Got Free is a fearless, semi-magical-realist queer coming-of-age story that also won the 2013 Lambda Literary Award for debut fiction. And Moya Bailey liked it.

In a review at Lambda Literary, Dawn Robinson writes:

“I will not give you all of the salient details of this layered, complex, and absorbing novel in this brief review—no spoilers here. Still, I need to ask you a few clarifying questions. Are you interested in a novel that is simultaneously critical social commentary, ghost story, murder mystery, and queer love story? If you were interested in such a novel, would it matter to you that the craft of the writing is deceptively plain, and in that simplicity, achingly poignant, laser-like in its facility and effect? Me too. I love that.

Finally, if you found out that the author was a fiercely brilliant black queer woman, who layers on discovery, insularity and secrets with a deft touch, would you be queuing up to get a copy of this book? Thought so.”

8. Nevada, by Imogen Binnie

Nevada is about what happens when you work at a used bookstore and love your bike more than your girlfriend and drink maybe too much and take drugs but inject only estrogen and break up with your girlfriend and travel across the country.

In an interview with Dan Fishback on Emily Books, Binnie says:

“But with Nevada specifically I was thinking a lot about what kinds of stories we are told and therefore get to tell about trans women and how they almost never have much to do with the lived experiences of, like, myself, or most of my friends. So this project, for better or worse, was just to tell a different story. And also, to write a book I wish I could read. So while writing the book wasn’t for an audience in a specific way, I wrote it with an awareness of (and anger at) the boring tropes we see in trans narratives over and over.”

7. Bi: Notes for a Bisexual Revolution, by Shiri Eisner

Eisner describes Bi as her “attempt to create a radical bisexual politics, and it is deeply informed by intersectionality, feminism, trans politics and race politics – not in the least because I myself am a trans* person of color.” She addresses bisexual politics through multiple facets and is informed by feminist, trans* and queer politics, theory and activism.

A.J. Walkley calls it a “definite must-read” and writes:

“The research Eisner has done for this book is clear from the beginning and the result is an incredible historical review of the bisexual movement from a whole host of perspectives and views, as well as clear ideas for revolutionizing it from here on out. With chapters on bisexuality, monosexism and biphobia, privilege, feminism, women and men, trans*, radicalization and what Eisner calls the “GGGG movement,” or the Gay-Gay-Gay-Gay movement, readers are exposed to the major issues that have impacted bisexuals over the years and those that are affecting us today.”

6. One Hundred Apocalypses and Other Apocalypses, by Lucy Corin

Lucy Corin’s experimental collection of 100 short stories about the end of the world has received high praise from the Rumpus and the LA Review of Books, which calls it ”

In an interview with the Rumpus, Corin says:

“I decided I wanted to write an apocalyptic narrative, but the more I thought of it, it seemed bizarre and untenable to me to pick one, so I just didn’t.

I was interested in beginning and ending something as quickly as possible, as many times as possible, as a way of getting at a cultural fantasy life that has to do with the apocalyptic. Nobody can live in this culture and not realize that people really love this shit. We just love it. And so I started writing one after another and investigating it myself and talking to people about their own apocalyptic fantasy lives.”

5. Excluded: Making Feminist and Queer Movements More Inclusive, by Julia Serano

In Excluded, Julia Serano (author of Whipping Girl) discusses how queer and feminist movements challenge sexism but also police gender and sexuality, and what to do about that.

In an interview with Persephone Magazine, Serano says:

“Obviously, all these forms of sexism and marginalization are different, and I am not trying to conflate them or imply that they are all the same. But in studying them, it seems clear that there are parallels between all of them — in the way that they are enforced, and in the way that the marginalized group tends to react to their circumstance. Rather than merely petition for the inclusion of each excluded group on a one-by-one basis (as I did in Whipping Girl, and as many others before me have done), I wanted to try to get at the root of why we tend to create double standards and hierarchies, and how we can learn to recognize and challenge them in a more general sense. And I wanted to offer possible solutions that will help to reduce exclusion and marginalization in all cases, whether in the straight-male-centric mainstream or within our own queer and feminist communities and movements.”

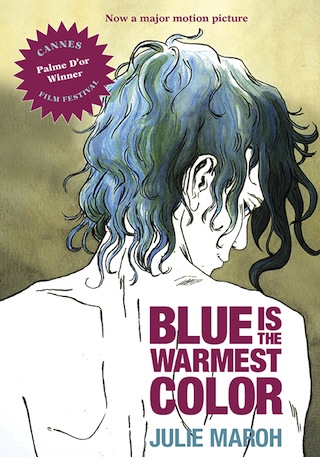

4. Blue is the Warmest Color, by Julie Maroh

Everyone’s been talking about the film that won the Palme d’Or at the 2013 Cannes Film Festival for months, and it’s been getting a lot of criticism for its rather extended lesbian sex scene. But the graphic novel the film is based on is sweet and lovely and significantly less male gazey.

In a review at Slate, June Thomas writes:

“Maroh, who was just 19 when she started the comic, manages to convey the excitement, terror, and obsession of young love—and to show how wildly teenagers swing from one extreme emotion to the next. The graphic novel also contains some stirring sex scenes. […]

Ultimately, Blue Is the Warmest Color is a sad story about loss and heartbreak, but while Emma and Clementine’s love lasts, it’s exhilarating and sustaining. In the scene reproduced here, Emma tells the infatuated Clementine about her coming-out process and her relationship with her girlfriend, Sabine.”

3. My Education, by Susan Choi

The latest novel from Pulitzer Prize finalist Susan Choi is about a grad student who begins an affair with her professor’s wife, and who then reflects on the affair 15 years later. In the New York Times, Emily Cooke calls it “elegantly written,” and writes:

“Choi has taken seriously the sexual love between two women who see themselves as straight. This choice of subject matter is an exciting one, for if a number of the great novels of the past century have been stories of gay love, no really adequate literature of bisexuality exists. Regina does not concern herself with the terms ‘lesbian’ or ‘bisexual,’ and she is nonchalant about the sex of her new lover. […] In love of great intensity and depth the specificity of the beloved can overwhelm any category he or she belongs to — and Regina swears that her feeling for Martha is ‘so unto itself it could not refer outward, to other affairs between women or even between human beings.’”

2. Hild, by Nicola Griffith

Set in violent seventh-century Britain, Hild tells the story of the pre-sainthood St. Hilda of Whitby, a girl who establishes herself as the seer to a ruthless king who finds her indispensable — until he doesn’t. It’s impossible not to love Nicola Griffith — she’s also the author of the feminist sci-fi novel Ammonite, the suspense-thriller-lesbian-romance The Blue Place, and lovely defences of why good sex in literature is important and Hild’s (bi)sexuality.

In an interview with herself at the Nervous Breakdown, Griffith says:

“As soon as I picked up her story–she was working out the weave of seventh-century British politics, tracing influences to their source–I thought, This is where I belong. […]

This story is epic in many ways–wars, dynasties, revenge, friendship, religious power struggle, ethnogenesis, sex, risk, joy–but in others it’s not. There’s no Meanwhile, a thousand leagues away in the point-of-view of a character you’d forgotten existed…, for example. Hild is in every single scene.”

1. The Feminist Porn Book, edited by Tristan Taormino

The Feminist Porn Book already feels like it’s been around for years just because it should have been — it fills a hole in contemporary feminist writing so big that I almost feel bad making a joke about filing holes.

The book features feminists from the porn industry and academia, including Susie Bright, Candida Royalle, Betty Dodson, Nina Hartley, Dylan Ryan, Jiz Lee, April Flores and more, talking about where feminist porn has been and where it might go. In an interview with Salon, Taormino says:

“One of the things we’re responding to is that there’s this notion that certainly is propagated by anti-porn feminists and other people, which is that there is one thing called porn with a capital ‘P.’ And it’s monolithic and we can qualify it in all these different ways and say this is what it looks like and this is what it does. As Constance says, ‘That’s just not true.’ What there is is a whole series of pornographies with a lowercase ‘p,’ and that’s what we have to look at and investigate. There is no one thing, and she even challenges the notion that there is a clear division between mainstream porn and independent porn, or mainstream porn and feminist porn, because there are feminists working within the mainstream porn industry and then there are feminists working independently, and there are non-feminists working independently, and vice versa. They’re all over the place.”

If your favorite book isn’t included here and you’ve got feelings about that, please comment in all-caps using as much punctuation and self-righteous indignation as possible! Or just tell me about what I should read next.